Gravity, it’s the law?

A look back on the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s theory of general relativity and how researchers have proved him wrong.

A Hubble picture of the galaxy NGC 5584 featuring a Type Ia supernova. Courtesy of National Geographic.

In the month of November, we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and while we can appreciate how the brilliant scientist effectively changed our fundamental understanding of the universe, new research has begun to question some of his claims.

In 1905, Albert Einstein determined that the laws of physics are the same for all non-accelerating observers. This became known as his theory of special relativity.

This new theory introduced a new framework for physics and proposed new concepts of space and time. As a result of this, he determined that space and time were interwoven into one continuum which he appropriately name “space-time”.

Einstein then spent 10 years attempting to include a force opposite to gravity into his new equation but published his theory of general relativity in 1915 without it thinking it wasn’t necessary at the time. Einstein’s theory of general relativity tells us that gravity is not quite the force Isaac Newton had envisioned. Einstein proposed instead that gravity is actually the bending of space and time by mass and energy. This discovery led to the widely accepted theory of Big Bang, which establishes the birth of our expanding universe some 14 billion years ago.

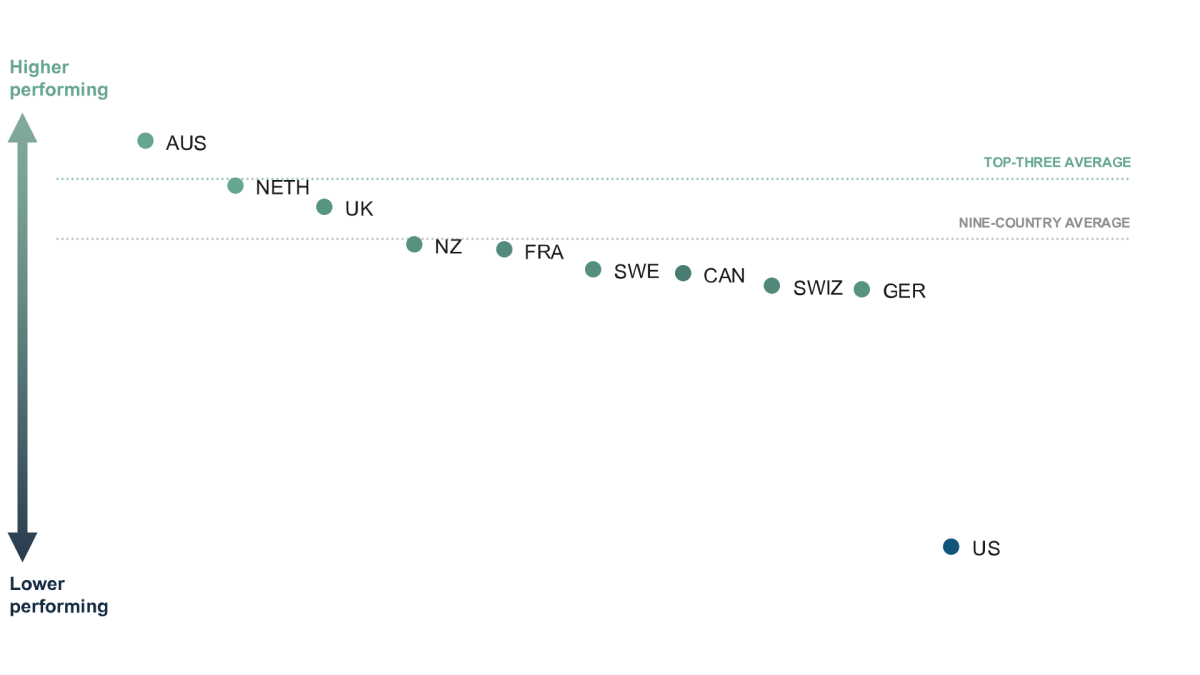

According to Einstein’s definition of gravity as an all commanding force, astronomers believed that the expanding universe was completely bound by gravity and would eventually slow its expansion to a stop. However, in 1998, Saul Perlmutter and Adam Riess of the U.S. and Brian Schmidt of Australia discovered that the universe is not only expanding, it’s speeding up.

This new discovery called “dark energy,” which won them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011, completely contradicted all previous predictions of the universe. According to the researchers, it seem as if something was overcoming gravity and pushing everything in the universe farther away at an increasing speed. These findings have long since been confirmed by other research groups.

New measurements now show that dark energy accounts for about 74 percent of substance in the universe and current studies of dark energy conclude that its effects will eventually dominate the universe. Scientists predict dark energy will isolate different galaxies and push them farther away from Earth.

But, before you go around looking for a bunker to wait for the end of world, you should know that scientists don’t have all the answers yet.

To this day, scientists are still trying to pin down exactly what dark energy is, “Physicists are conservative. We don’t want to throw away our theory of gravity when we might be able to patch it up,” says Nobel co-winner Riess, an STScI cosmologist to National Geographic News during an interview about his recent findings and Nobel win. “Basically it all comes down to the fact that there’s one relatively simple equation we work with to describe the universe.” he said, “Because we see this extra effect [dark energy], we can either blame it on the left-hand side of the equation and say we don’t understand gravity, or we can blame it on the right-hand side and say there’s this extra stuff.”

In November as we look back on Einstein’s theory of general relativity, we know that it provides a basis for sci-fi staples such as time travel, worm holes, parallel universes, and black holes. Scientists are still using Einstein’s theory to gain a better understanding of the universe around us. And who knows, maybe in another 100 years, another physicist will prove the theory of dark energy incorrect and we’ll be back to square one.

Your donation will support the student journalists of North Kingstown High School. Your contribution will allow us to distribute a print edition of the Current Wave to all students, as well as enter journalism competitions.